The English language is full of colourful idioms to spice up our discourse. In this article we’re going to have a look at expressions with animals in English, namely dog idioms.

‘Dog in the nighttime’, ‘a hot dog’ and ‘sick as a dog’ are familiar phrases to many of us. And indeed as our canine friends have long enjoyed a special relationship with us their human counterparts it should come as no surprise that it’s consequently reflected in a range of colourful, though sometimes obscure, idioms and expressions. Here I list some of my favourites as well as attempt to explain some of their coinage dates and both their original and/or current meanings.

A ‘top dog’ means a person or thing in a position of authority from a victory in a competition while an ‘underdog’ is a competitor thought to have little chance of winning a contest. Before the days of electric saw mills all timber had to be cut by hand as the bottom sawyer stood in the pit and got covered in sawdust (hence under-dog) while the top sawyer (top-dog) was more fortunate and guided the saw as it cut.

A ‘top dog’ means a person or thing in a position of authority from a victory in a competition while an ‘underdog’ is a competitor thought to have little chance of winning a contest. Before the days of electric saw mills all timber had to be cut by hand as the bottom sawyer stood in the pit and got covered in sawdust (hence under-dog) while the top sawyer (top-dog) was more fortunate and guided the saw as it cut.

Meanwhile a ‘black dog’ is a metaphor for depression; it derives from as early as the Latin poet Horace who wrote that to see a black dog with her pups was a bad sign and since then a black dog has often signified the Devil. Churchill also famously referred to his depression as his ‘black dog’.

‘It’s a dog’s life’ means a life of total indolence where the individual may do as he or she pleases, like a cosseted dog; originally the term referred to the hard life of the working dog in times when dogs were not pampered as pets, but were kept as watchdogs or hunting animals, not as pets. First recorded in the 16th century it seems to have kept the sense of ‘a life of misery or subservience’ ever since while ‘in the doghouse’ means in disgrace or out of favour and comes from Peter Pan, the 1911 book by J. M. Barrie. He used a plot device in which the father of the family, Mr. Darling, consigned himself to the dog’s kennel as an act of remorse for inadvertently causing his children to be kidnapped; there’s an alternative theory which is that doghouse is chiefly an American term and just refers to someone who is out of favour being sent out alone into the cold.

‘Every dog has its day’ means everyone will have good luck or success at some point in their lives. It seems first to have come from Richard Taverner in 1539 and later in 1600 in Shakespeare’s Hamlet with: “the cat will mew and dog will have its day”. A similar Shaekspearean contribution is ‘dogs of war’, meaning either the havoc that comes with military conflict or mercenary soldiers. It comes from the bard’s play ‘Julius Caesar’ with the line “let slip the dogs of war” referring to hunting dogs being unleashed to pursue their prey. Other references to dogs and days are ‘dog-days’ are days of great heat and refer to the Roman calling of the six or eight hottest weeks of the summer (considered to be between July 3rd and August 11th). They believed that Sirius the dog-star rose with the sun and added to the heat and so dog-days were a combination of the heat of both the dog-star and the sun.

More obscurely perhaps are ‘dog in a manger’ which refers to a churlish fellow who will not use what is wanted by another nor let the other have use of it; it alludes to the fable of a dog that fixes his place in a manger and would not allow an ox to come near the hay. ‘To see a man about a dog’ is used as an excuse or as an apology for one’s imminent departure or absence and which typically acts as a euphemism for going to the toilet or to buy a drink: it originally referred to betting on dog racing. ‘A shaggy dog story’ is a long, rambling story or joke, typically one that ends either in a deflating anti-climax or with an atrocious pun; from the 1930s, it comes from an advertisement in a British newspaper either for a competition to find the shaggiest dog in the world or for the loss of a very valuable pet in the form of a rather shaggy dog.

Other canine idiomatic allusions to dog racing are ‘to go to the dogs’ which means to deteriorate shockingly, typically in behaviour or moral standing and which derives from the fact that attending greyhound racing was once deemed likely to expose a person to moral danger and risk incurring considerable financial loss. And there’s also ‘to let the dog see the rabbit’ meaning to let someone get on with work that they are ready and waiting to do and which derives from greyhound racing where the dog chases a mechanical rabbit around the track.

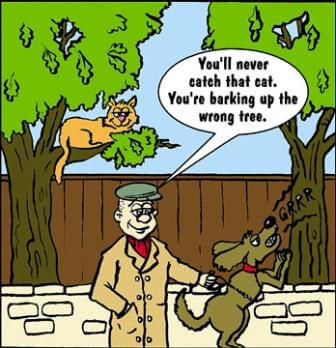

And then there’s their renowned act of barking which brings us ‘bark up the wrong tree’ meaning to have misunderstood something and then to pursue the wrong course of action. The phrase alludes to the mistake made by dogs when they believe they have chased a prey up a tree only for the game to have escaped by leaping to another tree. There’s also ‘barking mad’ used to suggest raving insanity and often shortened to ‘barking’. It’s an early 20th century phrase that stems from its link to rabid dogs who demonstrate their diseased state with their howling and yapping. And well-known is ‘one’s bark is worse than their bite’ meaning someone is not as ferocious as they appear or sound. This phrase was a proverb by the mid-1600s and a similar association between barking and biting arises in the earlier 13th century proverb (“a barking dog never bites”).

As for the process of eating, a ‘dog’s dinner’ is a mess or a poor piece of work and alludes to the image of a dog’s meal of jumbled-up scraps while ‘dog eat dog’ refers to a situation of fierce competition in which people are willing to harm each other to succeed; it refers to a mid-16th century proverb: “dog does not eat dog”. This list is not exhaustive though I trust not exhausting to the point of you, the reader, becoming ‘dog tired’ as in utterly worn out, alluding, as does its variant ‘dog weary’, to the image of a dog exhausted after a long chase or hunt. We’ll be back soon to share more expressions with animals in English, be on the lookout!

Article written by Break Into English contributor Adam Jacot de Boinod

Adam Jacot de Boinod worked for Stephen Fry on the first series of QI, the BBC programme. Adam is the author of The Meaning of Tingo and Other Extraordinary Words from around the World, published by Penguin Books.